How the criminal justice system interacts with brain injury, and impacts upon the brain-injured

The importance of identifying a suspected or actual brain injury in a developing brain cannot be underestimated. Our brains define who we are. Each brain is unique. The ability of the brain to disguise the effects of trauma, develop new neural pathways, and strive to overcome adversity is both a positive and a negative.

Those in education will be all too familiar with the scenario of a child returning to school having suffered head trauma, and that child then disguising the effects of the brain injury as nature takes over and the fight for survival begins and “return to normality” resumes. Dr Sian Rees’ comments in that regard will resonate with so many in the education sector, and, hopefully, inspire others in the education sector to reflect upon their own experiences in the classroom. If the subject of the hidden effects of brain injury becomes a staff room topic for discussion, then that cannot be a bad thing, can it?

Our understanding of early years development and brain injury

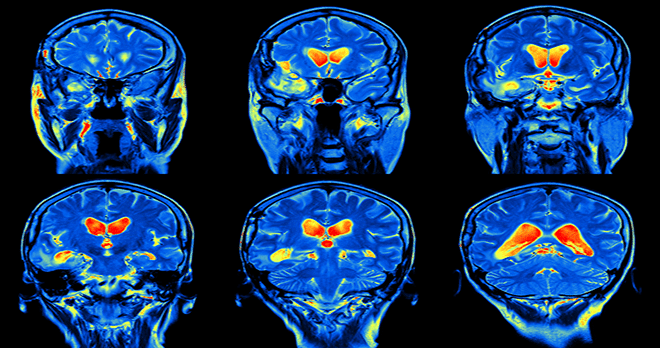

Advances in neuroscience have led to a greater understanding of the importance of our brains and how they function. There is still quite some way to go, however as our greater understanding develops, so we can develop support mechanisms and pathways to help those who suffer from the often-hidden disability that is the effects of a brain injury.

As a child progresses through their formative years, their personality develops. As we mature, we all respond to the structures and support received throughout our formative years. Personalities take shape, people develop and learn rapidly. Perhaps one of the most basic lessons humans learn is the fight or flight response, in other words assessing risk in real time with a view to self-preservation. I am sure we can all remember an experience in the playground where things might have been getting out of hand and we had to judge whether to walk away or stay involved. I am not sure that all of us on reflection would admit to making the right decision! An as Dr Sian Rees said in our article on early years development: “Making choices is very difficult. Your working memory tends to be shortened by a brain injury. So your ability, or rather lack of ability, to hold things in working memory, so that you can make a choice, is impaired, hence you will not be able to make wise choices”.

The change to the ability to assess risk and exercise judgment is one of the many issues that can follow brain injury. Whilst there are many of us in the population who exercise poor judgment in this regard, there are also children whose brain injury has caused this issue to develop where it would not previously have been a problem. Surrounding those children with the structure and support to restore and develop the skills to understand why this function is no longer working will help their development and integration into society. Failure to do so will only lead to outcomes as described by Dr Alyson Norman and Dr Rees.

The other enormous benefit of identifying brain injury in children is the ability to then educate families both in respect of the support that can be provided at home; educating the family as to what has happened to their child, and giving the family hope for the future.

The ‘slippery slope’ of undiagnosed brain injury and its links to crime

The impact of the pandemic has raised the profile of mental health, if indeed it needed raising. Whilst many who struggle with mental health issues are fully aware of the causes of those issues, it is possible to develop a wide range of psychiatric and psychological conditions as a result of a brain injury that is less obvious at first, or even second, glance. There is a scary, slippery slope that awaits. Dr Alyson Norman's account of her personal experiences provides a prime example of the contribution of brain injury to that scenario. One theme that presents time and time again is a lack of understanding that a brain injury has occurred at some point in the past, and the crisis point which has been reached is the result of the issues created by the brain injury. Poor judgment and risk assessment can lead to poor life choices, social isolation, lack of structure, purpose and meaning to life leading on to serious mental health issues.

Prof. Huw Williams’ research into the incidence of brain injury in our prison population has astonished everyone with its results. “In the prison population what we found was that about 60% had some kind of brain trauma history and 17% had severe brain injury”, Prof. Williams explained to us, “so that’s one or two in ten prisoners who have a significant brain injury and another four or five in ten prisoners have mild brain injuries, but often on repeat; so they’ve often had multiple mild brain injuries”.

Arguably one of the most infamous ‘victims’ of brain injury is Derek Bentley. It is reported that in 1937, aged just four years old, Derek suffered a serious brain injury to the extent that it caused brain damage and left him with epileptic seizures. This was obviously at a time before MRI and CT scanning. Derek Bentley was the last man to be hung in the UK, aged 19, having been convicted of a crime. It is also widely reported that Derek had a ”mental age of 11” and that he had suffered a further head injury during the Second World War.

"To quote Prof. Williams, those in charge of the prison service are "basically running brain injury units without adequate resources"."

It is clear that on the fateful night when a police officer was murdered, Derek Bentley was taking part in extremely risky behaviour. Whilst our criminal justice system has moved on considerably since these times, anti-social and risky behaviour nevertheless remains an enormous problem, as Prof. Williams’ research highlighted. To quote Prof. Williams, those in charge of the prison service are "basically running brain injury units without adequate resources".

Many victims of brain injury are extremely vulnerable to exploitation. Where the ability to distinguish right from wrong, to make good judgements as opposed to indifferent or bad ones has been diminished, it does not take much imagination to foresee the demise of the brain injury victims’ behaviour into criminal activity. As Prof. Williams said when we spoke to him “the prison population is full of people who have problems inhibiting themselves and stopping themselves doing something, so if they feel like doing something, ‘Oh my God, I’m finding it hard to stop’. They also have trouble paying attention to things at the same time; that’s the mild brain injury”. Given that many victims of brain injury struggle with setting boundaries and understanding the risks they may be about to take, having a criminal justice system that relegates brain injury victims to incarceration and a peer group who will often exploit and harm them cannot be in the best interests of those brain injury victims.

Developing the right pathway for brain injured individuals

It is therefore refreshing to see our Government has acknowledged that there needs to be an ABI pathway established and work is being done on that at the moment. One would hope that this will incorporate reference to the criminal justice system to identify a different pathway for brain injury victims.

One of the many reasons that incarceration is the wrong pathway for someone with a brain injury is that often they do not understand the effects of their brain injury and have just accepted life in the way it appears to them. If following a brain injury one is unable to understand that a certain behaviour is likely to lead to a run-in with the criminal justice system, and nothing is done to help that person, then repeat behaviours will occur.

Prof. Williams’s research highlights the fact that our prison system is simply not capable of supporting those with brain injuries. The prison system must cater for the whole spectrum of society. In this case, one size definitely does not fit all. The importance of sleep, rest and avoiding overstimulation is well understood for those with a brain injury.

Prisons are noisy environments, and whilst there is a basic structure, the noise and demands on prisoners to follow a routine does not assist those with a brain injury. Fatigue is a common issue suffered by those with a brain injury. Overstimulation and poor sleep architecture can exacerbate fatigue which in turn reduces the resilience of those with a brain injury and behaviours deteriorate yet further.

It will become apparent to other prisoners within a very short space of time that the person with a brain injury is vulnerable to exploitation, and that will of course happen. There is limited, or no, neuro-rehabilitation available to prisoners. In any event many prisoners are the undiagnosed victims of brain injury.

Prof. Williams’s research highlights the fact that a different pathway could be developed for young people with a brain injury, so that they are not exposed to prison life and receive the support and understanding which would lead to educating them about their brain injury. That can only be a good thing for the brain injury victim, their families, and society as a whole. As Prof. Williams says himself, “Wouldn’t we be better off spending money earlier to manage a kid in school so they don’t end up being bullied, then ending up bringing a weapon to school and then getting into all kinds of problems after that? Wouldn’t it be better if we had better systems in place to manage that rather than pay the price of sending someone to prison in three, four, five, six years’ time and all the costs associated with then getting other problems, so developing a drug disorder on top of everything else (or whatever it is). We’d be better off, wouldn’t we?”

"Wouldn’t it be better if we had better systems in place to manage [a brain injury] rather than pay the price of sending someone to prison"

It is widely understood that the importance of our formative years cannot be underestimated. Supporting families to understand the effects of a brain injury in a child and how they can help structure and support the child's life is well within our grasp as a society. What is happening though is that children with brain injuries go undetected too often. There are too many gaps in our health and social care systems, and by the time the young person comes into contact with the criminal justice system it would often be the case that there has been no identification of brain injury or education.

Furthermore, the financial burden of the impact of crime is astonishing and comes at a time when our healthcare system is challenged to the extreme both in terms of the ability to function and the cost to the taxpayer. Identification of children living with brain injuries is therefore essential.

Rehab support is essential

The next area of contention is in rehabilitation – where is the support for people who have recently experienced brain injury? That is vital for anyone, and not least young people.

The concept of the rehabilitation prescription was introduced in 2010. In practical terms it became effective in 2013 and applies to all patients who are admitted to hospital for more than 24 hours.

The prescription recognises that children up to age 16 will have different clinical needs; nevertheless the rehabilitation prescription document is designed to cover the first six months post-discharge to include all settings and services required, and transitions along the rehabilitation and recovery pathway.

There is no question that if the rehabilitation prescription is fully funded then it will resolve many issues for victims of brain injury. Implementing appropriate therapy and neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric support for victims of brain injury will inevitably educate victims, their families and their support network of the effects of the brain injury and how these could be managed as well as understood. It will be interesting to follow the development of the Government's ABI strategy given the unequivocal savings that supporting those with a brain injury can make to our healthcare and social services sectors.

"There is no question that if the rehabilitation prescription is fully funded then it will resolve many issues for victims of brain injury."

It has been refreshing to see the NHS RECONNECT programme being adopted by NHS Foundation Trusts. The program seeks to work with people about to be released from prison and helps them make the transition to community-based services providing them with the health and care support that they need.

As Prof. Williams points out, in the world of brain injury where fatigue, poor decision making and dysexecutive problems are rife, a simple text reminder to the brain injured victim reminding them of the appointment with the probation officer will mean greater chance of that appointment being kept, and a greater understanding of the support that is needed to allow brain injured victims to carry on their pathways. He gave the example of a pilot programme they ran with Devon & Cornwall Police: “We identified more than half of them had a moderate/severe brain injury. So now the community worker and the police are going, ‘Hang on, you had a brain injury didn’t you? So maybe if we texted you before we have your next probation meeting to make sure you know when and where it is and would that work for you?’ and, ‘Yeah, thank you’. So you’re having a conversation then about putting support in place so people aren’t breaking the terms of their licence; that’s a key thing.”

Recent developments in our understanding of brain injury

The impact of the pandemic on those living with brain injury has been enormous. The systems that we have in place to assist with engagement have been stretched to breaking point. Social isolation and burnout are regularly reported in the press and with particular reference to our understaffed Healthcare sector. Whilst we may be in a perfect storm, now is the time to plan for when the storm passes. There has been a higher incidence of strokes as a result of contracting Covid-19 virus, as well as ongoing chronic fatigue issues.

Another well publicised trend is an increase in domestic violence, something that is only recently being understood in the context of brain injury.

We know from current research that there is a high incidence of brain injury in the female prison population, many of those women citing domestic violence as the cause of their brain injuries. It is notable that there seems to be a very clear difference between someone who has suffered a head injury as a result of a fall and a trip to hospital, as opposed to someone who has been the victim of domestic violence. In the latter case, the reporting of the violence is sadly less likely whereas in the former a visit to a GP or hospital is likely.

There are thousands of women living with the effects of brain injury who have not reported their injuries because they were caused by domestic violence. Reaching out to those women has to be a priority so as to help educate them and understand the issues that can follow brain injury, in the same way that helping children identify their undiagnosed brain injury is a priority.

We have come a long way along the road of discovery into the incidence and effects of brain injury, and there is still some way to go. Nevertheless, increasing the exposure of these issues to the wider public can only assist in educating and supporting those who find their lives touched by the effects of brain injury.

Discover the other Untold Stories of brain injury

Brain injury remains little-understood by wider society. Here we hope to share some of the key Untold Stories of brain injury and how they affect individuals and their families.