A closer look at retinal stem cells – a potential cure for retinal disease?

In humans, retinal tissue does not regenerate in the way that much of the body’s other tissues will. That means that, once tissue in the retina has been damaged, the effects are permanent.

Because of its inability to regenerate, diseases of the retina are usually progressive and irreversible. So where possible, clinicians have aimed simply to slow disease progression – with considerable success in the case of ‘wet’ macular degeneration. However, historically, retinal disease has been difficult to treat.

The development of stem cell technology over the past decade has offered real hope for patients suffering from retinal disease. Stem cells can be used to replace damaged tissue, thereby (potentially) not merely slowing but actually reversing the gradual destruction of the retina.

Retinal medicine has been at the forefront of stem cell developments for several reasons: firstly, the retina is immuno-privileged (so there is less chance of the patient’s immune system rejecting the cells). Secondly, you only need a relatively small number of cells (hundreds of thousands rather than millions or billions) to make real functional difference – the retina is not a big place. Thirdly, there is often little else that clinicians can offer.

What are the potential problems with retinal stem cell therapy?

Setting the potential benefits aside, stem cell therapy in the retina is not straightforward. A reliable source of stem cells is needed: this sounds obvious, but it’s a highly complex consideration for an “off the shelf” treatment – whatever process is used, has to be capable of being scaled up and manufactured.

Then there’s the question of what cells to use. There are different types of stem cell, each of which has varying properties: after years of research, it’s still not wholly clear which of these works best.

There were also concerns that the cells might either die off once introduced, or proliferate wildly – in effect acting like a tumour.

Then there’s the problem of cell placement: you can’t just introduce cells into a specialised environment like the retina and expect them to “get on with it”. They have to be integrated into the local tissue, and vascularised (that is, they need a blood supply).

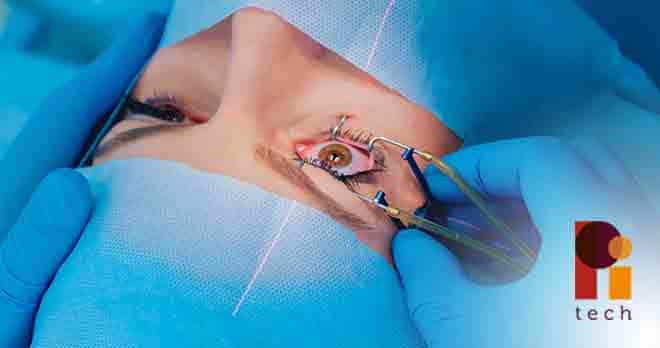

Finally, there are surgical challenges. Placing stem cells reliably and safely in a tiny area requires complex equipment and a hugely experienced surgical team.

How has it worked in practice?

Research has progressed rapidly and many of these challenges are being met. Last year, a phase 1 clinical trial in London was reported. Two patients with advanced macular degeneration (a condition which obliterates central vision) were treated.

The trial implanted a sheet of pre-arranged stem cells. This sheet was then grafted onto the back of the eye in a microsurgical procedure.

One patient recovered 19 letters of text on an eye chart; the other recovered 17 letters of text, an astonishing leap in visual acuity. Unfortunately this is still at a developmental stage, and wider trials are needed before it can be rolled out.

Is it all good news for patients?

In a word: no. Some unscrupulous organisations have disgracefully attempted to profit from patients who are losing their sight and who typically feel desperate.

There have been reports that several clinics in the US have started injecting adipose (fat) cells harvested from patients. Unfortunately for the patients who have been injected with it, there is little evidence to suggest that these cells work especially well in the eye.

Furthermore, the clinics reportedly aren’t inserting pre-prepared sheets of cells using established micro-surgical techniques. Rather, they’re just injecting some cells (whether or not the injections are sited correctly isn’t clear from the reports). More alarmingly, there have been cases in which clinics have allegedly suggested that patients have both eyes treated simultaneously. Most reputable clinicians would tell any patient that that is a terrible idea. Stem cells are a new technology and if anything were to go wrong, then you will have caused the patient to lose all vision and taken away the “plan B” that the other eye represented.

Unsurprisingly, the reports about these clinics refer to some patients being blinded – the very outcome they were trying to prevent. The only justification I can see for treating both eyes simultaneously is a financial one.

It’s also important at this point to stress that true blindness is relatively rare. In conditions like macular degeneration, patients will typically retain some vision, albeit that central vision is obliterated. Most patients also retain some degree of independence and, with training, can learn to make the most of their remaining vision. If such a patient is therefore left completely blinded, then s/he will be far worse off than would otherwise have been the case. It is difficult to overemphasise the disservice such clinics risk doing to their patients.

It is an alarming thought that such private clinics could set up in the UK. If they do and they are not regulated – and fast – then the consequences to individual patients could be catastrophic.

It is appalling to think that desperate patients can be used to make a fast buck, and I would strongly urge anybody contemplating such a procedure in the private sector to talk it over with their ophthalmologist first – they will be more than happy to provide objective advice. And if anyone offers to treat both of your eyes with stem cells (for a price), then, whoever they are and whatever their purported qualifications – just walk out.